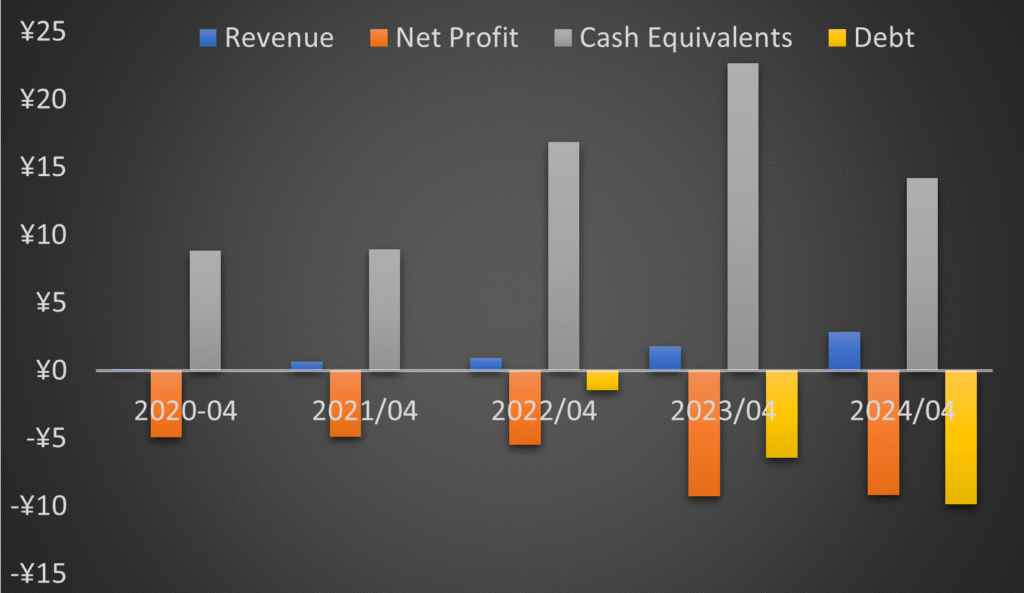

| Market Cap: ¥93.8B TTM revenue: ¥5.7B YOY return: -40.2% |

CEO: Nobu Okata Cumulative pay: ¥500k (est) Shareholder value created: -¥18.9B |

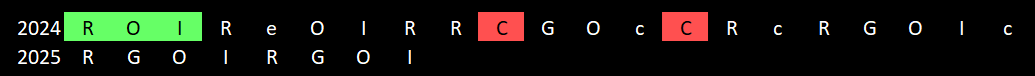

Forecast effort: A Forecast accuracy: C |

|

Japan-based Astroscale ambitiously went public with aims to reach breakeven in 2026. Potential revenue streams include co-developing satellite buses with Mitsubishi, pursuing in-situ space situational awareness (ISSA) projects, and providing end-of-life services for deorbiting satellites, particularly for OneWeb’s constellation. Astroscale also focuses on geostationary satellite life extension contracts, a business line that is already highly contested. Achieving 2026 breakeven requires quickly winning multiple life extension and deorbit contracts. After going public, Astroscale quickly scaled down 2025 revenue forecasts. Reliance on government contracts, the uncertainty surrounding the commercial viability of satellite deorbiting services, and competition in the GEO life extension market make their path to profitability challenging. Reaching their goals requires successful execution across multiple business lines and a favorable regulatory environment, particularly for end-of-life services.

2 Minute Version

- Founded in 2013, Astroscale is a global company headquartered in Tokyo, Japan with significant presence in the United States, UK and Israel. Astroscale is commercializing on-orbit servicing and ensuring the safe and sustainable development of space.

- The company offers a range of services, including end-of-life (EOL) satellite removal, active debris removal (ADR), life extension (LEX), and in-situ space situational awareness (ISSA).

- Astroscale aims to address the growing problem of space debris and extend the operational life of existing satellites, working with government and commercial entities like JAXA, U.S. Space Force, ESA, OneWeb, and Intelsat.

- Astroscale targets long-term gross profit margins in the mid-30% range and operating profit margins in the mid-20% range.

- Of Astroscale’s four business lines, only LEX seems currently commercially viable. But it is already heavily contested.

- No commercial firms appear ready to pay market rate to remove old satellites or debris. Thus Astroscale’s ADR and EOL segments currently appear dubious aside from government-funded proof-of-concept projects.

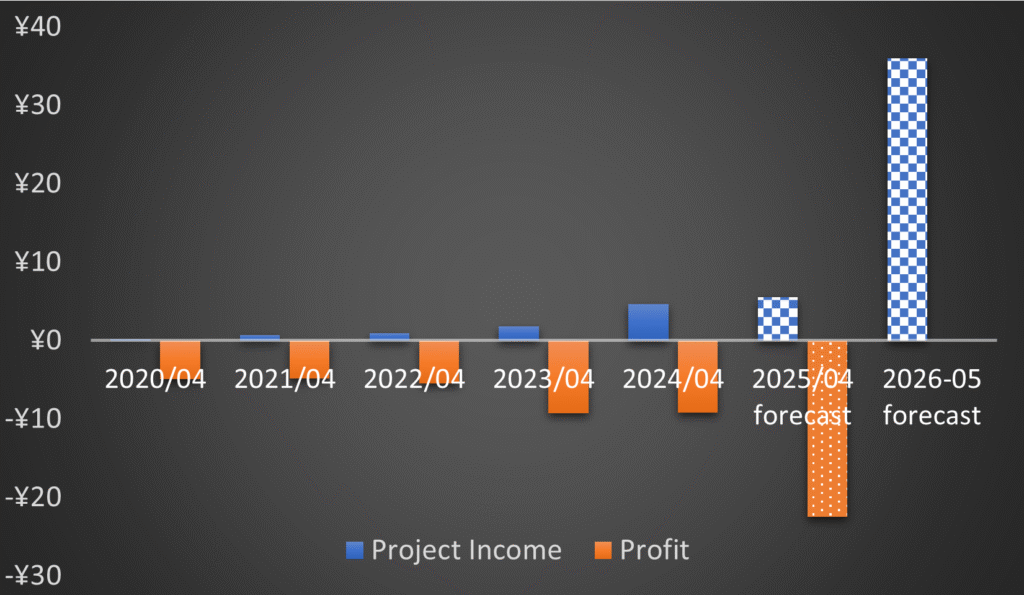

- For fiscal year 2025, Astroscale initially projected 12 billion yen (approximately $80 million) in “project income” and operating losses of approximately 17.9 billion yen (around $116 million). Soon after going public, Astroscale downwardly revised this to 5.5 billion yen and losses of 22.5 billion yen.

- Astroscale aims for 2026 revenue of 36 billion yen (around $240 million), allowing for operating breakeven that year. With the 2025 forecast scaled back, this target too seems ambitious.

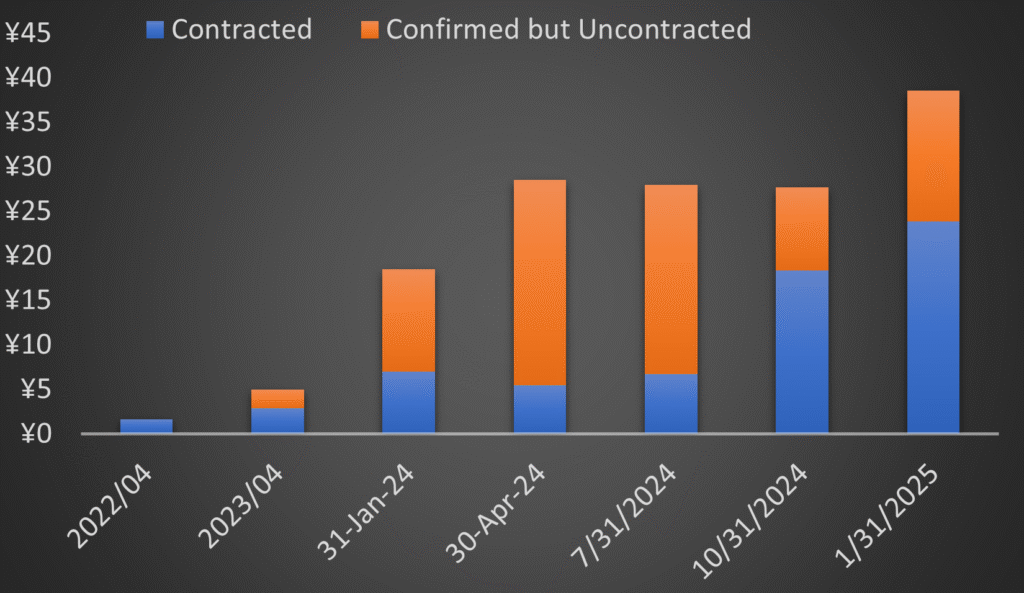

- As of October 31, 2024, Astroscale held 27.8 billion yen (approximately $177 million) in cash and equivalents. Their total backlog, including confirmed but uncontracted projects, stood at 27.6 billion yen (approximately $185 million).

- Achieving projected profitability heavily relies on securing major contracts (like COSMIC Phase C, LEXI-P, and K-program) and the development of a sustainable commercial market for its pioneering services.

Astroscale’s four business lines

Astroscale relies nearly entirely on government funded contracts for revenue. Although reporting revenue in just one segment (“in orbit servicing”), Astroscale identifies four separate business lines.

1. End-of-Life (EOL) satellite removal

Astroscale sells magnetic docking plates to satellite manufacturers intended for pre-launch satellite integration. Satellites normally operate, conserving enough fuel so at end of mission they can propel downward and deorbit, burning up in the Earth’s atmosphere. However, upon malfunction, satellites essentially becoming stuck in orbit. In such event, Astroscale plans selling deorbit service to satellite operators. Astroscale will launch its own satellite, attach to the customer’s malfunctioning satellite docking plate and pull the satellite to a lower orbit where deorbiting naturally occurs due to atmospheric drag.

The market for satellite deorbit services is early stage. Operators generally leave spent satellites in orbit. These satellites pose collision risk with others, threatening creationing of large debris fields that could potentially make certain orbits uninhabitable to other satellites. Astroscale represents in investor relations materials a plan to charge customers like OneWeb $8-13 million per satellite deorbit. No commercial customer has yet to pay Astroscale (or any other firm) to deorbit a satellite. OneWeb is an early adopter of docking plates, equipping its first-generation satellites with Astroscale’s docking plates. Future legal or regulatory change is likely necessary for the EOL market to become viable. Astroscale management appears to agree.

The FCC presently requires satellite operators to deorbit satellites within 5 years of mission end. Dish was supposed to deorbit EchoStar-7, a broadcast satellite in geostationary orbit, by moving it up 300km to a graveyard orbit. Due to low fuel, Dish failed to properly retire EchoStar-7 300km above the GEO belt, moving it only 122 km. The FCC fined Dish $150,000 for failing to properly deorbit EchoStar-7. It is unclear how strong the financial incentive is to pay Astroscale $8 million to deorbit a malfunctioning satellite when FCC’s fine is only $150,000.

Astroscale secured a contract totaling €32.6 million for its ELSA-M mission, to deorbit a faulty OneWeb satellite. (Originally, when the contract was first awarded, the target satellite to be deorbited was not yet chosen; a OneWeb satellite was decided later). The contract receives significant funding from the ESA and UK Space Agency. However, Astroscale disclosed that for Phase 4 of this contract they recorded a 3,204 million yen loss provision (approximately $20.8 million). Astroscale effectively is itself paying a significant amount of the costs to deorbit a satellite for OneWeb.

Market Take: Major planned operators of LEO satellites are SpaceX and Amazon Kuiper. Both launch into low-LEO orbits where atmospheric drag is strong enough to naturally deorbit satellites in about 5 years (5-7 years for Amazon), even if propulsion malfunctions. These major constellations will likely not be customers for deorbit services. High-LEO satellite constellations are few, but include OneWeb, Lightspeed, SDA, and Rivada (should it get off the ground). Should the regulatory environment change, future operators launching satellites could be required to deorbit all faulty satellites as a condition to constellation approval. Such costs would then be budgeted into initial project costs, creating an actual commercial EOL removal market. Until then, it seems unlikely any commercial firms will be calling Astroscale to deorbit their satellites.

2. ADR – Active Debris Removal

Astroscale’s CEO Nobu Okada likes citing the 23,000 objects greater than 10cm cataloged in Earth’s orbits as potential debris and targets for removal. Astroscale plans launching satellites to capture this debris and lowering it out of orbit. Sounds simple. Astroscale already has two ADR contracts. The Japanese government is providing Astroscale up to 13.2 billion yen ($91 million) for ADRAS-J2, aimed at removing a spent Japanese upper rocket stage from orbit. The UK is paying Astroscale $46-62 million for COSMIC, a project which will remove two inactive British satellites from orbit.

The idea of removing space debris is not novel. Commercial competitors include:

- Clearspace SA, which received an €86 million ESA contract to remove Vespa (Vega Secondary Payload Adapter), a defect satellite launched in 2013.

- Clearspace also receives funding from the UK Space Agency on a space removal contract.

- U.S. based startup Turion has also received development funding from SDA for debris capture. Turion uses electronic ion thrusters for cost-effective propulsion.

Market Take: There will not be $91 milion contracts to remove each of the 23,000 softball and greater size objects of space debris that CEO Okada often talks about. However, if the most threatening debris is targeted for removal, JAXA, NASA and other space agencies have determined removing five to ten debris objects per year will significantly improve the orbital space environment over the course of the next 200 years.

LeoLabs’s Darren McKnight is an authority on quantifying and cataloging the riskiest debris in space. But of the most threatening objects in orbit, all of the top 10, and 36 of the top 40, are Chinese and Russian origin. China and Russia are not racing to hire Astroscale (or anyone else for that matter) to remove their debris. Present contracts from the UK and Japan target significantly less threatening debris for removal. For space debris removal to be seriously addressed, new international law or the creation of a new international system regulating space debris is likely required.

Even if political hurdles are surmounted, near-term paying customers creating a market to remove debris is a stretch. Aside from SpaceX’s contract to remove the ISS, Astroscale’s and Clearspace’s 13 billion yen and €86m respective contracts likely represent the high water mark for this market. Future contracts for debris removal will likely before of progressively lower amounts.

3. LEX – Life Extension

Approximately 550 satellites orbit the Earth in geostationary orbit (GEO). These satellites are typically much larger and more expensive than average LEO satellites. About 20 to 30 GEO satellites decommission annually, usually after meeting or exceeding their 15-year design life. Many, if not most, are not decommissioned due to technical failure but rather the depletion of their fuel supply, which is required to maintain orbit.

SpaceLogistics, an Astroscale competitor and a first-to-market provider, estimates that 50% of these satellites remain functionally sound but cease operation due to a lack of fuel. Thus, a market of 10-15 potential customers per year for GEO satellite life extension appears reasonable.

Life extension works by launching a mission extension satellite, full of fuel, to grab and reposition a customer’s GEO satellite that has run out of fuel. The mission extension satellite uses its thrusters and fuel to maintain the orbit of the customer’s satellite, allowing it to continue operations in its designated GEO orbital slot.

Astroscale entered this business in 2020 by acquiring the Israeli firm Effective Space Solutions. In December 2023, Astroscale signed a non-binding $121 million term sheet with a customer for a LEX (Life Extension) deal termed LEXI-P. Astroscale also represents that a $215 million LEX project with an unknown customer, termed LEXI-G, is in the pipeline. Further details about LEXI-G are sparse.

While GEO satellite life extension is opportune presently, it may become less so in the future as GEO satellite orders decline while LEO satellite launches increase. Noting this, Astroscale has obtained one LEO satellite refueling contract from the U.S. Government – APS-R ($25.5 million) – and is working on acquiring a second from the Japanese government, the K-Program (¥10.9 billion).

Market Take: Overall, LEX presents the strongest opportunity for Astroscale’s revenue growth. A market already exists proving GEO satellite operators will pay for life extension services. However, Astroscale must compete with three major competitors for GEO business.

- Northrop Grumman’s subsidiary SpaceLogistics LLC has already successfully docked with and returned two Intelsat satellites to service. Intelsat ordered two more life extensions from SpaceLogistics. Australia’s Optus also ordered life extension service from SpaceLogistics in 2022, originally slated for a 2024 launch but pushed back to 2026.

- Intelsat also ordered another life servicing mission from competitor Starfish Space in 2024, set to launch in 2026.

- And ESA awarded Italy’s D-Orbit a €119 million contract (“subsidy”) to demonstrate the ability to dock with, maneuver, and release a satellite in GEO.

4. ISSA – In-situ Space Situational Awareness

Astroscale also has a business line of launching satellites to approach and photograph other satellites and objects in space. Their first, and well-publicized, ISSA project was ADRAS-J, which approached and photographed a spent rocket stage in low earth orbit. For this, Astroscale received ¥12.7 billion (approximately $12.7 million) from the Japanese government, likely not enough to cover costs. The ADRAS-J mission’s purpose was to inspect and assess this debris for potential removal. The mission demonstrated key technologies for active debris removal (ADR) and provided detailed observations of the target, including fixed-point and fly-around imaging.

This is the least technically challenging of Astroscale’s four business lines but likely with the least immediate commercial potential. While ADRAS-J’s mission demonstrated the technical feasibility of approaching and characterizing space debris, the commercial market is still nascent. The mission highlighted the need for advanced navigation techniques and multi-sensor systems (VISCam, IRCam, and LiDAR) for precise approaches and detailed imaging. Currently, the customers willing to pay for such services are likely limited to governments, as satellite operators are not yet incentivized to pay for object inspection. A key aspect of the commercial potential lies in improving orbital safety, preventing collisions, and prolonging the operational life of satellites.

However, competition exists. Starfish Space also aims to provide on-orbit debris inspection and recently won a $15 million contract from NASA for the same. Turion Space also plans three space domain awareness satellites. And Old Space player Thales Alenia Space has received a demonstration contract to make an inspection satellite that can grab an object and perform up-close inspection.

Financial Disclosures

Astroscale’s financials yield few insights. The company is still in growth stage, with huge R&D investments and significant losses. Astroscale management at IPO initially forecasted a quick exit from the growth stage, planning to reach breakeven in FY 2026. (Astroscale’s fiscal calendar ends April 30th.)

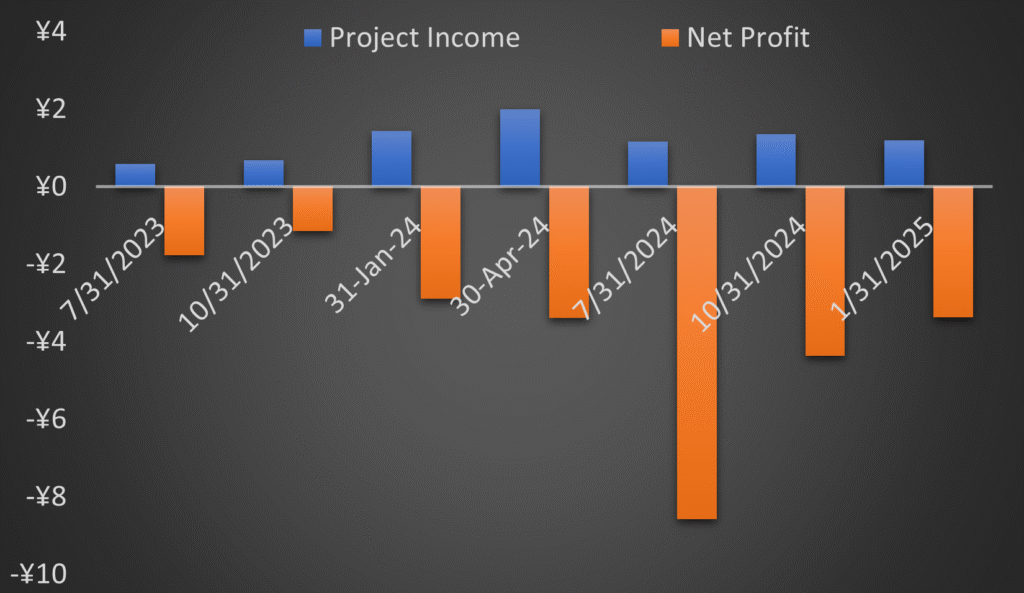

Astroscale reports revenue and “project income.” Project income is the sum of revenue and government subsidy payments received. Income here is a bit of a misnomer, but accounts for total payments received from grant and contract projects. Plotted quarterly to-date show no growth. It is no surprise Astroscale revised its forecast downward.

Astroscale reports two categories of backlog: (1) Contracted and (2) Confirmed, but not yet contracted. The latter includes projects that Astroscale is pursuing for which there are no other competitors. Astroscale’s total backlog, including unconfirmed amounts, stands at about 38.5 billion yen as of January 31, 2025. Even if this total backlog is realized, this does not amount to the “project income” Astroscale forecasts it needs by April 2026 to breakeven.

While its usefulness is uncertain, Astroscale’s project income per employee has grown to approximately $63,000. Project Income has grown at a rate approximately 10 times greater than the rate of growth for headcount.

Path to profitability

Astroscale aims for gross profit margin in a mid-30% range and operating profit margins in the mid-20%. Astroscale’s initial strategy involved achieving ¥18 billion “project income” in FY 2025, and then doubling to ¥36 billion in FY 2026. Towards this, in FY 2025 Astroscale plans on winning COSMIC Phase C, LEXI-P, and K-program contracts. Astroscale aims future projects to be entirely self-funding and profitable, thereby reducing the impact of loss-making contracts on cash flow. This is to drive 2025 gross profit to near breakeven. However, 2025 operating losses are, per plan, projected to reach higher levels than in 2024. To double project income in FY 2026, Astroscale states they need to win an additional LEX contract and/or EOL (deorbit) contracts. Should Astroscale meet this plan, they claim investors will see significant gross profit and near operating profit breakeven in FY 2026. (See below- highly unlikely since Astroscale have failed to timely achieve even its first LEX contract.)

Per their initial plan, Astroscale forecasted ¥18 billion (approximately $120 million) in “project income” in 2025 and ¥36 billion (approximately $240 million) next year. Although not supplying a specific number, Astroscale published a chart in an August 2024 investor deck depicting approximately ¥17.9 billion in operating losses in FY 2025. According to management, this project income growth would enable Astroscale to reach operating profit breakeven in FY 2026. This forecast was apparently too aggressive. Astroscale updated it after its IPO, cutting forecasted FY 2025 project income from ¥18 billion to ¥5.5 billion. Astroscale claimed delays pushed revenue outward. The current plan now requires explosive growth in FY 2026. Judge the likeliness of this as you will.

Per plan, R&D costs will significantly decrease in FY 2026 as LEXI-P and ADRS-J2 pre-project costs get re-categorized as COGS. (However, development costs for projects like LEXI-P and ADRS-J2, regardless of being categorized as R&D or COGS, have the same impact on operating profit.) As Japanese government grant contracts conclude, these costs currently accounted for as R&D will also cease. (However, government-reimbursed research projects, do not impact whether Astroscale reaches breakeven.) Astroscale plans maintaining R&D related to future project pre-development.

Presently, according to Astroscale’s August investor slides, FY 2025 R&D costs are projected to include approximately ¥1.5 billion in “pure R&D” costs plus ¥5.1 billion in pre-development R&D costs. If in FY 2026, (1) Astroscale maintains pure R&D levels, (2) halves FY 2025 pre-development R&D costs (it appears their internal goal is cutting this much further), (3) maintains non-R&D SG&A costs at 2024 levels (historically growing, so unlikely), and (4) achieves a goal of 30% profit margin on “project income,” the math shows Astroscale requires ¥36 billion of project income that year for operating profit breakeven. This number exactly matches Astroscale’s forecasted amount of project income in 2026.

Astroscale achieving its FY 2026 forecast: balancing ambition with market realities

Astroscale’s ability to break even in FY2026 is contingent upon obtaining $240 million of 30% margin project income that year. Assuming Astroscale acquires the COSMIC Phase C, LEXI-P, and K-program contracts and met its prior FY 2025 revenue forecast (of $120 million), these and other multi-year contracts could be assumed to provide recurring revenue in FY 2026. This leaves Astroscale needing an additional $120 million in 30% margin revenue in FY 2026. Astroscale’s August 2024 investor presentation lists no prospective projects slated to start in FY2026. But it does identify certain sources of potential future revenue that we will analyze.

- Co-project with Mitsubishi to develop satellite buses: Reports suggest Astroscale is providing their docking plates for these satellites. What work beyond this Astroscale will provide, and the fraction of future revenue due to Astroscale, is unknown. The commercial satellite industry is incredibly competitive, and margins are not high. However, the satellites developed with Mitsubishi are to be sold to the Japanese government, which has budgeted $2.1 billion for a military satellite constellation. NEC historically has been Mitsubishi’s main satellite manufacturer competitor in Japan. But it appears iQPS, Synspective and Axelspace are also eying providing earth imaging satellites under these contracts.

- Two potential In-situ Space Situational Awareness (ISSA) projects: One potential contract is with an unnamed space agency, and the other potential project(s) is with an unnamed government defense agency. Astroscale’s first ISSA contract, ADRAS-J, was a $13m Japanese government contract and almost certainly operated at a large loss. Astroscale’s second ISSA contract came in the form of an $80m SBIR grant from the Japanese government. If the two new contract sources are also both in Japan, and if the projects go forward, Astroscale likely faces little domestic competition. The only announced potential competitor is IHI Corporation, who announced a partnership with Northrop Grumman to develop satellites to observe other satellites. However, IHI’s plan is to operate in GEO, not LEO. Such missions in LEO have additional challenges over GEO, due to discontinuous satellite communication.

- EOL Life missions: Astroscale notes 568 satellites equipped with docking plates launched between 2021 and 2024. These are primarily, if not entirely, OneWeb’s Gen-1 satellites. Estimating a deorbit failure rate of 7-8% and Oneweb paying $8-13 million to deorbit each satellite, Astroscale could see $318-$591 million in potential revenue. Astroscale’s existing ELSA-M contract, funded in part by the ESA and UK Space Agency, aims to deorbit a single OneWeb Gen-1 satellite in 2026. Future orders from OneWeb are likely contingent upon Astroscale successfully demonstrating deorbit in ELSA-M.

- GEO satellite life extension contracts: Astroscale’s first potential successful contract is for the LEXI-P life extension project, for which Astroscale signed a non-binding term sheet with a private satellite company in December 2023. LEXI-P is valued at $121 million. Astroscale has not disclosed the customer, and a final contract is not signed. The LEXI spacecraft is to launch in 2026. A successful demonstration of LEXI-P likely opens up future order possibilities with other customers.

Satellite co-manufacturing with Mitsubishi

The Mitsubishi satellite co-development project does not seem a likely source of $120 million extra revenue in FY2026. Mitsubishi will likely manufacture the satellites themselves, as Astroscale hasn’t announced construction of a satellite manufacturing plant. Even they together score a large contract, most revenue seemingly will go to Mitsubishi.

Deorbiting OneWeb malfunctioned satellites at EOL

Contracts to deorbit OneWeb satellites contributing significantly towards $120 million in FY2026 revenue also warrant skepticism. The 7-8% failure rate estimate may actually be accurate. By comparison, Iridium launched 95 satellites for its first LEO constellation between 1997 and 2002. (In 2019, Iridium finished replacing the original original satellites with Iridium Next Gen.) However, for Iridium’s first generation constellation, 35 satellites malfunctioned and are stuck in orbit (37%). So estimating a 7-8% malfunction rate for OneWeb Gen-1 satellites may not be far off.

However, whether OneWeb will pay Astroscale to deorbit its malfunctioned satellites is another question. At $8-$13 million per satellite, this is not cheap. And furthermore paying in FY2026 is even more uncertain. Astroscale UK Managing Director Nick Shave suggests future regulation may drive the market for Astroscale’s deorbital services. No current regulation exists which requires OneWeb to deorbit defunct satellites. Astroscale is targeting constellations as prospective customers for this service. However Astroscale’s own Chief Operations Officer Chris Blackerby said, “We recognize the operators don’t see a current impetus to bring [their debris] down.”

Iridium, a signing member (with OneWeb and SpaceX) on the Satellite Orbital Safety Best Practices document, noted best practices include “Actively and expeditiously manage the deorbit of LEO satellites that are reaching the end of their useful mission life.” As mentioned they have 35 satellites malfunctioned and stuck in orbit. Iridium CEO Matt Desch stated that paying to deorbit old satellites offers his company little financial benefit. He famously estimated willingness to pay just $10,000 to deorbit each satellite. With Iridium offer just $10k to deorbit each of its malfunctioned satellites, why think OneWeb will pay Asrtoscale $8 to $13 million? OneWeb’s parent company Eutelsat operates at a loss, so with money tight already paying for deorbiting seems far-fetched. They are not even fully paying for the deorbit of their first satellite. The ESA and the UK Space Agency are subsidizing Astroscale’s mission for this deorbit.

And then there is timing. If OneWeb does pay to deorbit its failed satellites, how likely is it payments start in fiscal year 2016? The math suggests it is possible. OneWeb designed these satellites with a 5-7 year design life and launches began in 2021. So satellites retiring as early as 2026 is reasonable to assume. However, satellites commonly outlive their original design life. Keeping with the Iridium example, their satellites were designed for 12.5 years but lasted 20. Airbus will build replacement satellites for OneWeb’s Gen1 in 2026 and launching afterward. Thus OneWeb’s existing constellation will likely remain functional until at least 2027. Whereas until then, certain satellites may malfunction and offer candidates for deorbiting service. But taken together, it seems extremely unlikely that EOL contracts to deorbit failed OneWeb satellites will provide any strong source of Astroscale revenue in FY2026. If OneWeb does pay to deorbit its failed satellites, it likely will be after 2026. And after Astroscale’s ELSA-M demonstration mission is successful.

GEO satellite life extension contracts

GEO satellite life extension contracts remain a strong opportunity for Astroscale’s growth. The market is established, proving GEO satellite operators will pay for life extension services. Northrop Grumman’s subsidiary SpaceLogistics LLC has already successfully docked with and returned two Intelsat satellites to life. Intelsat ordered two more life extensions from SpaceLogistics. Australia’s Optus in 2022 also ordered life extension service from SpaceLogistics, originally slated for a 2024 launch but pushed back to 2026. Intelsat also ordered another life servicing mission from competitor Starfish Space in 2024, set to launch in 2026. And ESA awarded Italy’s D-Orbit a €119 million contract (“subsidy”) to demonstrate the ability to dock, maneuver, and release a satellite in GEO.

After successfully demonstrating the operation of its LEXI servicer, Astroscale forecasts obtaining 1-2 similar GEO servicing contracts yearly from commercial and government customers. Astroscale estimates each servicer can achieve $121 to $215 million in revenue over a 15-year lifetime, paid in milestones. For its first mission, LEXI-P, Astroscale claims to be in advanced negotiation stages. The first customer remains unknown. Selling 1-2 servicing missions yearly is aggressive but not out of the question. Approximately 550 satellites are parked in GEO orbit, of which Astroscale estimates 20-30 retire annually. SpaceLogistics estimates that 50% of these satellites remain functionally sound but retire early due to lack of fuel. Thus, a market of 10-15 potential customers per year seems in line. Moreso than selling deorbit service to OneWeb, GEO life extension appears to be Astroscale’s most promising commercial market.

Summation

Back to the question of whether Astroscale can break even in FY 2026 by finding $240 million in 30% margin revenue. We think this is extremely unlikely. No basis yet exists to think OneWeb or other satellite operators are seriously considering paying Astroscale (or any vendor) $8-$13 million for EOL deorbiting. Absent a law, regulatory change, or litigation threat, little economic motivation exists for a commercial firm to bring down its defunct satellites from orbit. Case in point: Iridium. Astroscale UK Managing Director Nick Shave appears to agree that government regulation is needed to create a commercial satellite deorbiting service market.

GEO satellite servicing revenue seems much more opportune. A proven commercial market already exists, with two Astroscale competitors already signing contracts with five commercial customers. Astroscale’s own stated goal is 1-2 LEXI missions yearly. Discounting that its technology remains unproven, if Astroscale sells three missions, the top range of their price estimates gives about $43 million in revenue yearly across these missions. This would leave Astroscale needing to find $77 million additional revenue for FY 2026. Furthermore, LEX competitors Starfish Space and SpaceLogistics signed contracts for service missions two years ahead of the mission. (D-Orbit 4 years.) This does not leave much time for Astroscale to secure three launches and service deliveries by 2026. This explains why Astroscale needed more capital to fund its operations.

To put it another way, Astroscale forecasts $360 million in “project income”/revenue over FY2025 and 2026 to break even. Astroscale posted approximately $18 million in the first two quarters of FY 2025. This leaves $342 million needed over the remaining six quarters. Astroscale’s total backlog, including uncontracted backlog, totals $267.8 million. Even if Astroscale converted all its backlog to revenue over the next 6 quarters, they still come up short. May the force be with them.

Management guidance scorecard

Astroscale’s fiscal year ends April 30th, and in early 2024 they provided guidance on FY 2024 project income, operating profit, and income that Astroscale quickly met. Astroscale’s track record of providing reliable guidance to investors since has become suspect.

Initial FY 2025 guidance was apparently too high. Astroscale downwardly revised such forecasts after its IPO.

More significantly Astroscale has twice told investors that existing cash was enough sustain Astroscale until reaching breakeven. Specifically, Astroscale noted in its Q1 2025 financial statement that it held ¥27.3 billion in cash and equivalents as of July 31, 2024. This cash level, too, according to management, was enough to sustain Astroscale until reaching positive cash flow. This ended up untrue. Astroscale initiated a cash raise in May 2025.

CEO compensation and performance

In Japan, individual CEO compensation must be disclosed in cases where it exceeds a certain threshold (often ¥100 million, or ~$700k). Astroscale did not disclose specific compensation for CEO Nobu Okada. Thus his compensation likely is below this level.

Astroscale outlook and risk assessment

Astroscale’s future outlook appears highly ambitious and carries significant risk, primarily driven by its aggressive forecast to achieve breakeven by FY2026, contingent on securing an unlikely $240 million in 30% margin project income for that year. The company’s reliance on government-funded contracts is clear across its four business lines (EOL, ADR, LEX, ISSA), with a commercial market for End-of-Life (EOL) satellite removal appearing highly improbable without new regulation or stronger financial incentives, as commercial operators currently lack motivation. Even Astroscale’s initial ELSA-M mission is incurring substantial losses for Astroscale.

While Active Debris Removal (ADR) and In-situ Space Situational Awareness (ISSA) are technically demonstrated, their near-term commercial market potential remains limited, with current contracts being government-funded and unlikely to scale to the necessary revenue levels. The Life Extension (LEX) service for GEO satellites remains Astroscale’s most promising commercial opportunity, given an established market with paying customers. But Astroscale faces strong, proven competition (SpaceLogistics, Starfish Space, D-Orbit) and its own technology remains unproven, making the rapid acquisition of large, profitable contracts by FY2026 challenging, especially as contracts are typically secured years in advance.

Compounding these operational hurdles, Astroscale’s financial track record shows consistently large losses, substantial R&D investments, a significant downward revision of its initial FY2025 “project income” forecast, and an insufficient backlog to meet its aggressive FY2026 targets. Furthermore, management’s past guidance on cash sufficiency proved inaccurate, necessitating a recent capital raise, indicating a high financial risk in achieving its stated profitability goals.

What to look from Astroscale

Here are five key points for investors to watch regarding Astroscale’s future:

- Operational Demonstration Successes and Scalability: The successful demonstration of Astroscale’s technologies, particularly the ELSA-M deorbit mission and LEXI-P life extension, is critical. Beyond initial demonstrations, watch for signs of successful commercial scalability – the ability to transition from one-off government-funded projects to efficiently executing multiple, profitable commercial missions, which is essential for sustainable growth and reaching their long-term margin goals.

- LEXI-P Contract Finalization and Revenue Recognition: Investors should closely monitor the announcement and terms of the LEXI-P life extension contract. Astroscale had previously forecasted revenue from this project to be realized in the fiscal year ending April 2025. The lack of an announced contract to date indicates either a further delay in revenue recognition or potential cold feet from the prospective customer, which could significantly impact their FY2026 breakeven targets.

- Pace of Capital Utilization and Future Capital Raises: Given Astroscale’s history of significant R&D investments and operating losses, and the recent capital raise in May 2025, it’s crucial to observe the rate at which this newly raised capital is consumed. Investors should assess whether this funding appears sufficient to sustain operations through to their ambitious FY2026 breakeven target, or if the likelihood of another capital raise, with potential shareholder dilution, appears high.

- Commercial Traction for EOL and ADR Services: Beyond government contracts, watch for any concrete commercial breakthroughs in Astroscale’s End-of-Life (EOL) satellite removal or Active Debris Removal (ADR) services. The current market for these is largely driven by government grants and regulations, rather than commercial demand. Any actual paying commercial customers, or significant progress in regulatory frameworks that incentivize deorbiting, would be a strong positive signal.

- Achievement of FY2026 Project Income Targets: Astroscale has set an ambitious target of ¥36 billion in “project income” for FY2026. Investors should track their quarterly financial disclosures for evidence that they are on a credible path to achieving this figure, especially considering the recent downward revision of FY2025 forecasts and the substantial portion of this target still needing to be secured.

Recent News

-

iQPS misses post-Trump space stock run; plagued by two 2024 on-orbit satellite failures

QPS-SAR-6 fell out of orbit on November 17th, spending just 17 months of its 5 year design life in orbit. QPS-SAR-6 suffered failure in July…

-

AAC Clyde Space sells four more Starbuck power systems (€1.025m)

AAC Clyde reports sale of 4 Starbuck power systems, plus services, for €1.025m (approx. SEK 11.6 M). Revenue is expected to be recognized in the…